Affiliations

ABSTRACT

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic inflammatory disorder with heterogeneous presentation and clinical course. We present a case of a young female with an atypical presentation of SLE. A young woman with no known prior comorbidities presented with a history of chronic diarrhoea, vomiting, and weight loss, followed by generalized weakness. An extensive workup was done and she was diagnosed with lupus enteritis based on history, laboratory investigations, and imaging findings. She was given pulse therapy to which she responded very well. The case describes the importance of high clinical suspicion and timely intervention as well as adds to the evidence on a rare clinical entity of lupus enteritis.

Key Words: Systemic lupus erythematosus, Lupus enteritis, Autoimmune disorder, Chronic diarrhoea.

INTRODUCTION

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is a common multi-system autoimmune disorder involving a wide spectrum of clinical features. The most frequent presenting symptoms are musculoskeletal or cutaneous, followed by haematological, renal, cardiac, nervous system, and gastrointestinal tract.1 Gastrointestinal symptoms in SLE were first notified in 1895 and may range from vomiting and abdominal pain to diarrhoea. The magnitude of gastrointestinal involvement is also greatly variable, ranging from hepatitis, pancreatitis, and lupus enteritis (LE) to mesenteric vasculitis.2 LE was defined by the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG) in 2004 as vasculitis or inflammation of the small bowel, diagnosed based on clinical features supported by suggestive imaging and/or biopsy findings.3 LE may be prevalent in about 0.2-9.7%4 of patients diagnosed with SLE but LE presenting as the initial manifestation of the disease is quite rare.5 In addition, diagnosing LE without a prior background of SLE can be challenging.

CASE REPORT

A 21-year Asian lady presented to the Emergency Department with complaints of progressive generalised weakness associated with intermittent diarrhoea and vomiting for 6 weeks.

She had been having 7-8 episodes of watery, non-bloody, large-volume stools not associated with fever or abdominal pain. Vomiting was non-projectile, non-biliary, and non-bloody, small volume, exaggerated in the last 4 days. She was initially seen on an outpatient basis and prescribed antibiotics for these symptoms without any improvement in clinical condition. She also reported a weight loss of about 7 kg from baseline weight. Her appetite had been well initially but she was unable to tolerate diet for the past 4 days due to recurrent vomiting. She denied a history of rash, joint pains, hair loss, or oral ulcers. There was no recent travel history. She also denied having any allergies or addiction. There was no family history of tuberculosis or malignancy. Past medical history was significant for a second-trimester abortion of an unidentified cause about 2 months ago. She did not have any previous surgeries or blood transfusions.

On examination, the patient was vitally stable. She was a lean-built lady with vitiligo marks on her legs. She was alert and oriented to time, place, and person. On chest auscultation, decreased air entry was observed in the right lung base. The abdomen was soft and non-tender without any visceromegaly. There was no shifting dullness and gut sounds were audible. Sensory and motor examination was within normal limits.

Laboratory investigations revealed anaemia, severe hypo-kalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia, and metabolic acidosis (Table I). Based on history, clinical examination, and laboratory results, a differential diagnosis of celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and intestinal tuberculosis was made along with protein-losing enteropathy associated with SLE or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Further, workup confirmed malabsorption syndrome, so she was planned for an upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. Pre-procedure COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) came out positive, so the procedures were postponed.

Table I: Baseline laboratory investigations of the patient.

|

Tests |

Results |

Reference ranges |

|

Hemoglobin |

6.0 |

11-14.5 g/dl |

|

Hematocrit |

13.8 |

34.5-45.4 % |

|

Mean Corpuscular Volume |

108.7 |

78.1-95.3 fL |

|

White blood cells |

8.8 |

4.6-10.8 ×109/L |

|

Neutrophils |

86.6 |

34.9-76.2% |

|

Lymphocytes |

7.8 |

17.5-45% |

|

Platelets |

339 |

154-433×109/L |

|

Amylase |

291 |

28-100 IU/L |

|

Creatinine |

1.0 |

0.6-1.1 mg/dL |

|

Sodium |

141 |

136-145 mmol/L |

|

Potassium |

1.5 |

3.5-5.1 mmol/L |

|

Chloride |

108 |

98-107 mmol/L |

|

Bicarbonate |

16.9 |

20-31 mmol/L |

|

Calcium |

7.6 |

8.6-10.2 mg/dl |

|

Magnesium |

1.3 |

1.6-2.6 mg/dl |

|

Serum glucose |

114 |

80-160 mg/dl |

|

Total bilirubin |

3.0 |

0.1-1.2 mg/dl |

|

Gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) |

92 |

<38 IU/L |

|

Alanine Transaminase (ALT) |

47 |

<35 IU/L |

|

Aspartate transaminase (AST) |

126 |

<31 IU/L |

|

Alkaline phosphatase |

173 |

45-129 IU/L |

|

Lipase |

512 |

6-5 1U/L |

|

Prothrombin time (PT) |

13.3 |

9.3-12.8 seconds |

|

Activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) |

20.4 |

22.9-34.5 second |

Table II: Additional laboratory investigations of the patient.

|

Tests |

Results |

Reference ranges |

|

Stool analysis |

+14 pus cells |

|

|

Red blood cell folate |

1300.4 |

280-791 ng/ml |

|

Vitamin B12 |

>2000 |

>201 pg/ml Acceptable |

|

Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) |

715 |

120-246 IU/L |

|

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) |

47 |

0-20 mm/1st hour |

|

Reticulocyte count |

8.81 |

0.6-2.4 % |

|

Coombs test |

Positive (++++) |

|

|

Tissue Transglutaminase Immunoglobulin A (tTg-IgA) |

<0.5 |

Positive: >3.5 U/ml |

|

Tissue Transglutaminase Immunoglobulin (tTg-IgG) |

0.72 |

Positive: >3.5 U/ml |

|

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) |

Non-reactive |

|

|

Hepatitis B Surface Antigen (HBsAg) |

Non-reactive |

|

|

Hepatitis C Virus Antibody (Anti-HCV) |

Non-reactive |

|

|

Serum albumin |

2.5 |

3.5-5.2 g/dl |

|

Fecal calprotectin |

2.5 |

Negative <43.2 ug/g |

|

Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) |

1.150 |

Adults: 0.4-4.2 uIU/ml |

|

Anti- Nuclear Antibodies (ANA) |

Positive (Homogenous) |

|

|

Anti-double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid antibodies (Anti-DsDNA) |

1252 |

Positive ≥25 IU/ml |

|

Anti–Sjögren Syndrome A (Anti-SSA) (Ro) |

1.27 |

Positive >5.0 U/ml |

|

Anti–Sjögren Syndrome B (Anti-SSB) (La) |

0.54 |

Positive >12.5 U/ml |

|

Smith Antibody (Anti-Sm) |

0.81 |

Positive >5.0 U/ml |

|

Scleroderma Antibodies; anti-topoisomerase (Anti Scl-70) |

1.43 |

Positive >5.0 U/ml |

|

Anti-Cardiolipin Immunoglobulin M |

23.41 |

Positive >7.2 MPL-U/mL |

|

Anti-Cardiolipin Immunoglobulin G |

15.40 |

Positive >14.4 GPL-U/mL |

|

Lupus Anticoagulant screen |

51.5 |

31-44 seconds |

|

Spot Urinary Creatinine |

69 mg/dl |

- |

|

Spot Urinary Protein |

252 mg/dl |

- |

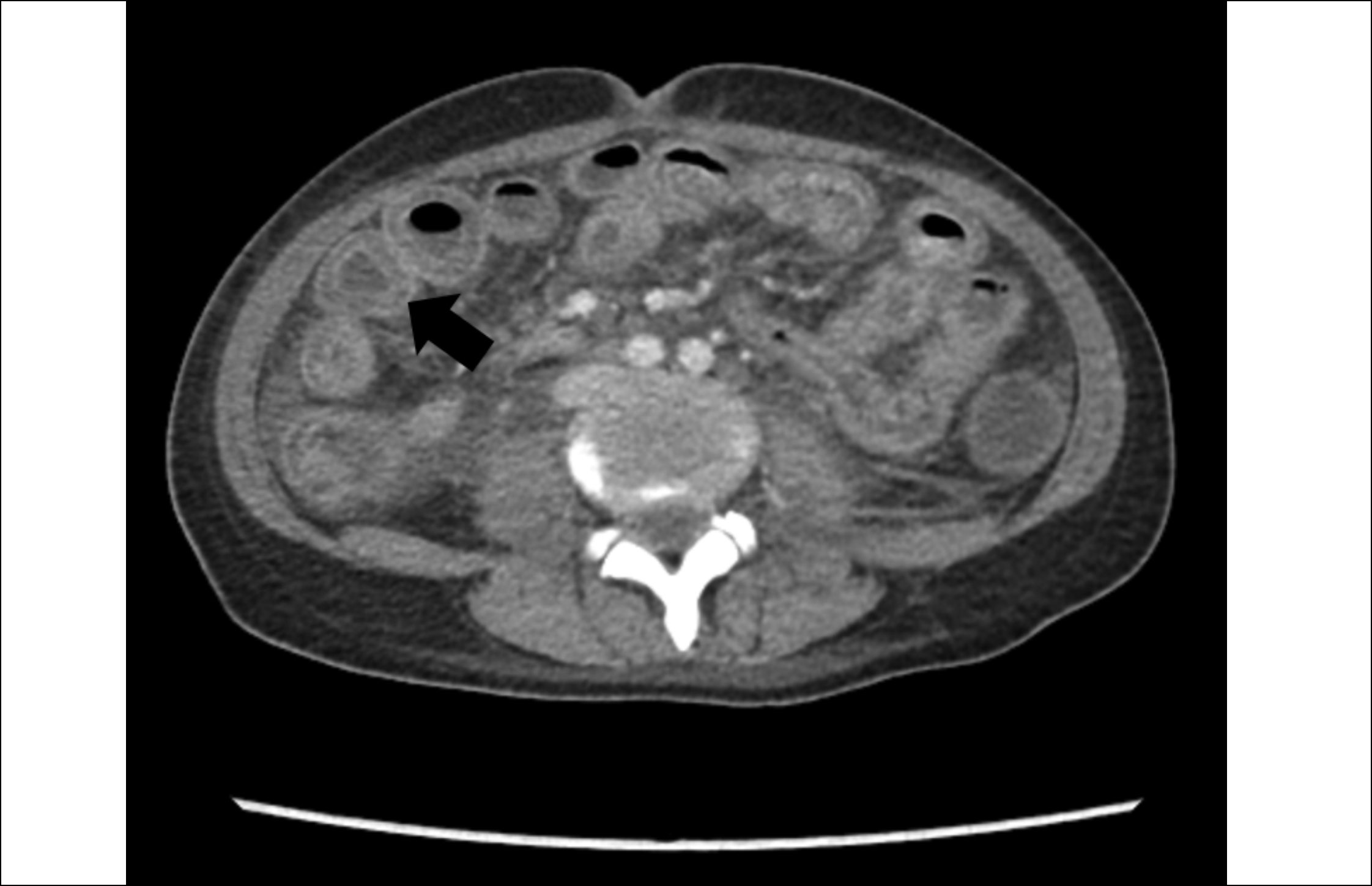

Figure 1: Computed Tomography (CT) scan (axial view) showing diffuse bowel wall edema and target sign.

Figure 1: Computed Tomography (CT) scan (axial view) showing diffuse bowel wall edema and target sign.

Figure 2: Computed Tomography (CT) scan (coronal view) showing diffuse bowel wall oedema and target sign.

Figure 2: Computed Tomography (CT) scan (coronal view) showing diffuse bowel wall oedema and target sign.

She underwent a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) abdomen which showed diffuse oedema of the stomach, small bowel, and large bowel with a positive target sign. Right-sided pleural effusion and mild ascites were also noted (Figures 1 and 2). Meanwhile, anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid antibodies (anti-dsDNA), lupus anticoagulant, and anti-cardiolipin antibodies came out positive (Table II). She was diagnosed with LE with associated anti-phospholipid syndrome. She fulfilled 8 of the 17 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) criteria including serositis, nephritis, hemolytic anaemia, lymphopenia, and presence of ANA, anti-dsDNA, and anti-phospholipid antibodies as well as a positive direct Coombs test. She was started on pulse therapy with intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g per day for 3 days. Her condition improved. She was discharged on oral prednisolone 30 mg twice a day with early follow-up.

DISCUSSION

This case reports an uncommon presenting feature of a commonly occurring disease. It emphasizes that despite being rare, LE is an important differential in patients presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms. It is crucial to identify and treat this condition timely as it may be associated with significant morbidity and mortality; hence, the index of suspicion must be kept high.

SLE is a heterogeneous disease in terms of its clinical presentation, evolution, and prognosis but its manifestation with LE is exceptionally scarce. LE was initially identified in 1980 and due to its heterogeneity and paucity of evidence, it has not been a part of the SLICC criteria for diagnosis of SLE.6 LE does not have characteristic clinical features and may present with diverse symptoms such as vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, ascites, or fever. The pathogenesis of the disease is poorly understood but immune complex deposition along with complement activation seems to be the driving force. The most commonly involved sites are the jejunum and ileum followed by the colon, duodenum, and rectum, respectively.7 Endoscopy may not be helpful in such cases due to non-specific findings and the diagnostic yield of histopathology is 6%; hence, CT abdomen with contrast is the gold standard for diagnosis of LE. Demonstration of bowel wall thickness >3 mm (Target sign), mesenteric vessel engorgement (Combs sign), and attenuation of mesenteric fat are the classical features of LE on imaging.8 Management includes complete bowel rest and intravenous methylprednisolone as the initial therapy. If this is ineffective, immunosuppression with cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate, or azathioprine should be considered.9 Surgical intervention must be considered for resistant cases. Prognosis is usually excellent as the disease is steroid responsive but relapse after initial improvement may be seen in up to 23% of cases.9 Involvement of colon and bowel wall diameter >9 mm have been illustrated as risk factors for recurrence. In case of delay in treatment, LE may lead to bowel infarction, bleeding, obstruction, and perforation.7 A high fatality rate has been observed with the disease. Recently, Liu et al.10 have established a lupus risk assessment model to predict the development of LE in patients with SLE. Its significance is still unclear; nevertheless, the model might turn out to be useful in the early identification of the disease.

In conclusion, this case highlights LE as the initial manifestation of SLE and the key importance of a CT abdomen in its diagnosis with a remarkable response to steroid therapy.

COMPETING INTEREST:

The authors declared no competing interest.

PATIENT'S CONSENT:

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION:

AR: Conceptualisation and manuscript writing.

ZH: Literature review and proof reading of the manuscript.

OP: Primary physician, diagnosed the case and gave final approval.

REFERENCES